Samuel Fuller, Late Hitchcock, Nicholas Ray, Late Ford & Douglas Sirk

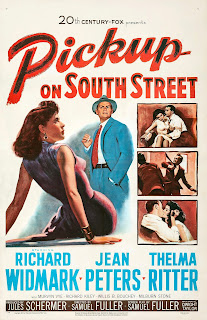

Samuel Fuller is known for his low-budget genre films that present controversial material. For example, 1964's The Naked Kiss is a film about a former prostitute engaged to a man who secretly is a child molester. Nearly 20 years later in 1982, Fuller made White Dog, a film about a dog trained by a white supremacist to attack black people who is then adopted by a young actress. But Fuller is perhaps best known for his 1953 noir Pickup on South Street, starring Richard Widmark. In the film, Widmark’s character Skip McCoy steals a wallet containing top-secret government information. The film asks questions about one's loyalty to their country and addresses a perceived Communist threat. Notice how Fuller omits dialogue in the following scene, yet still creates exciting tension through the use of a claustrophobic mise-en=scène, facial gestures, and point of view shots.

Samuel Fuller - known for low-budget films with controversial material

*The Naked Kiss

*Pickup on South Street

Pickup on South Street (Samuel Fuller, 1953):

Pickup on South Street Trailer - Click Here

TCM intro on fill and Fuller - Click Here

Alfred Hitchcock:

Mast and Kawin briefly discuss Alfred Hitchcock's films Rope (1948) and Strangers on a Train (1951) in which implied queer characters are not explicitly stated as being gay in the story and plot. Several of Hitchcock's films of the 1950s address sexuality beneath the surfaces of American life. In the process, Hitchcock offers dark, often sexual undersides of familiar movie stars such as Jimmy Stewart and Cary Grant. In Vertigo (1958), Stewart’s character Scottie attempt to reconstruct his female, sexual fantasy through Kim Novak’s character Judy. In 1954’s Rear Window, Stewart’s L.B. Jeffries practices a kind of fetishistic voyeurism by spying on the lives of his neighbors; he begins to suspect that his neighbor Thorwald (Raymond Burr) has killed his wife. Jeffries's spectatorship mirrors our own experience of watching movies, his vision sharing parallels with a movie camera. Trouble arises when the object of Jeffries's gaze steps out of the confines of the “screen” and into his own life. The following clip demonstrates Jeffries's voyeurism and view into the private lives of his neighbors.

Rope (1948) and Strangers on a Train (1951) "implied queer characters"

He also in the 1950s addressed sexuality 'beneath the surfaces of American life."

Shown in Vertigo (1958) and Rear Window (1954)

Rear Window (Alfred Hitchcock, 1954):

Opening clip we saw for class Click Here

Rear Window Clip - Click Here

The rebellious youth films of the 1950s such as The Wild One (1953) and Nicholas Ray’s

Rebel Without a Cause (1955) were a violent reaction against a decaying and diseased society. The youths rebelled against the sterility and conformity of normal adult life.

Another land-breaking style introduced was rebellious youth films in the 50's.

"The youths rebelled against the sterility and conformity of normal adult life."

The Wild One (1953) and Rebel Without a Cause (1955) for example.

Rebel Without a Cause Trailer - Click Here

The Western:

The Western remained one of the most exciting and entertaining genres of the transitional era. The films of Anthony Mann and Budd Boetticher maintained the conventional attitudes of the genre towards violence and killing. Violence was a legitimate means of establishing law and civilization and most westerns examine the essential human and social qualities that produced the American nation and its ideals. Other westerns of the 1950s began bending the conventions of the genre such as Nicholas Ray's Johnny Guitar (1954). The director perhaps most associated with the American Western, John Ford, delivered one of his most technically respected (and most racist) films with 1956's The Searchers. In the following clip, take note of how Ford shoots landscapes. The mise-en-scène of the scene showcases the limitless terrain Ethan (John Wayne) and Martin (Jeffrey Hunter) must cover in their futile search of family member Debbie.

The Searchers (John Ford, 1956):

Westerns were hugely popular in this transitional time period.

Directors Anthony Mann, Budd Boetticher, Nicholas Ray.

John Ford was a standout technically but had the most racist films.

His mise-en-scene showed lovely, vast terrain.

John Wayne in

The Searchers (John Ford, 1956):

A good clip - not one for class Click Here

The Searchers - Trailer - Click Here

Douglas Sirk came to Hollywood in 1937 from Germany because of the Nazi threat. He is perhaps most well-known for his melodramas of the 1950s, also identified as weepies or women’s films. Sirk’s films portray modern, bourgeois interiors that on the surface appear to be proper and banal. But Sirk’s films raise complex questions about class, race, and gender that aren’t usually explicitly emphasized by story or plot. Many scholars have identified Sirk’s films as modernist because of their hyperstylized visuals and self aware dialogue. In All That Heaven Allows (1955), a middle-aged widow (Jane Wyman) falls for a younger man (Rock Hudson) despite the disapproval of her friends and children. The film's visual design obviously isn't concerned with realism, which leads to the question if Sirk is purposely trying to subvert the conventions of the melodrama. Sirk calls attention to his mise-en-scene, using unnatural prismatic lighting and focusing on doorways, windows, and mirrors. In this scene, Cary's children give her a television for Christmas, signifying the promise that modern technology can remedy or dissolve her longing for her love Ron.

All That Heaven Allows (Douglas Sirk, 1955):

Douglas Sirk - came to Hollywood escaping Nazi Germany in 1937.

"Sirk’s films portray modern, bourgeois interiors that on the surface appear to be proper and banal. But Sirk’s films raise complex questions about class, race, and gender that aren’t usually explicitly emphasized by story or plot."

Considered a modernist because of hyperstylized visuals and self aware dialogue.

In All That Heaven Allows Jane Wyman's children had her break up with a younger man she loved and then give her a TV for companionship.

Rock Hudson in:

All That Heaven Allows (Douglas Sirk, 1955):

saw television scene for class Click Here

All That Heaven Allows - Trailer - Click Here

No comments:

Post a Comment